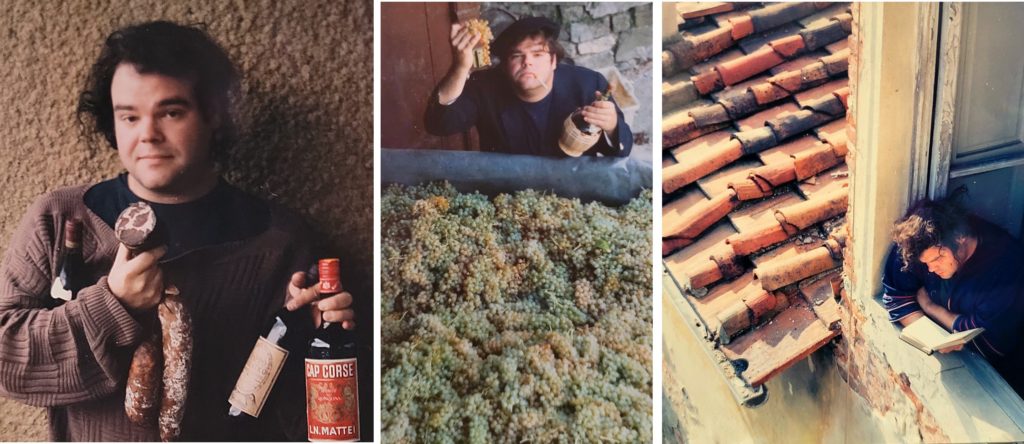

Anyone who would write a book like this would have to have served time as a Europhile, a creature of tattered-to-shreds Blue Guides and lost-count-of summer trips to Europe. I went to grad school in England (so that was five years of summers) and was fortunate enough to accompany student Study Abroad groups from my employer NC State University (another ten summers), and then I regularly went back under my own steam and pocketbook (another ten?), so yeah, I am saturated in Europe. With all that practice, you would think my command of languages would be better, but my fumbling in Italian, French, Spanish, German amuses my friends no end, so I have no incentive to improve.

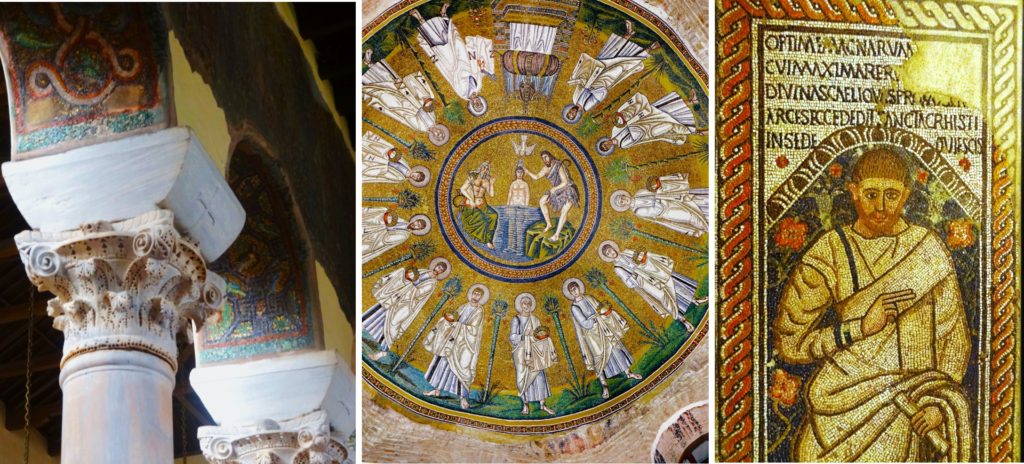

The character of Roberto Costa is not autobiographical (no trust fund for me, no heart issues, far less success as a lothario), but in some key way Roberto c’est moi… or, it makes more sense given his background, to say it in Portuguese: Roberto sou eu. Am I the only art history minor who felt he had discovered Europe? That there were so many cool cultural things that I thought I’d better had better write about and photograph so the whole inattentive world could hear about them! Roberto has his doomed Notebooks which is going to be Umberto Eco meets Marina Warner meets John McWhorter meets Barbara Tuchman—history, culture, language, food, geography, with lots of youthful pontifications and insights that he alone feels the mastery of. In the 1990s, like Roberto’s sister Rachel, I too felt like I might make a grand website with all the paleochristian mosaics in Europe…

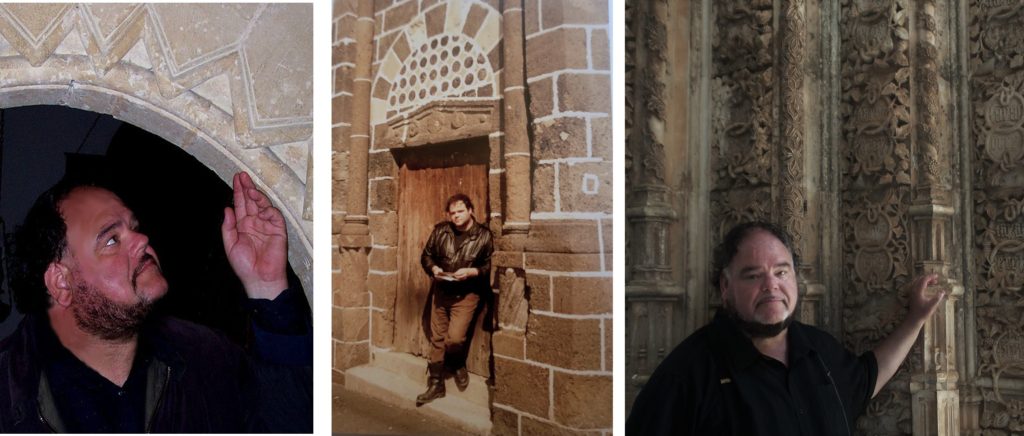

…or a catalogue of the best Romanesque tympana on medieval churches. From my twenties until last summer (I can’t get out of the habit) I have pursued every dot on the map of Wilfried Koch’s Baustilkunde, the ur-document, the Bible of medieval European treasures. I stood in medieval doorways for the photo for thirty-plus years in a row…

…only to be scooped by the “IMAGES” dropdown on Google search. Every miniscule village tucked away in the Pyrenees or Carpathians now has a hundred stock pictures showing the art treasures of the local church. No need for Roberto and Rachel Costa or Wilton Barnhardt to trouble themselves.

But these impulses did enrich my second novel, Gospel. Europe reads one way to the wide-eyed undergraduate visitor, who is mesmerized by the treasure and opulence of altars and stately homes and emperor’s summer palaces, eyes blinded by the jewels and gilding… but it looks another way to the more mature, better-educated traveler who knows just where the wealth of Belgium came from. The stately mansions of England with their Adam ceilings and Capability Brown gardens, funded by the slave trade. The older traveler thinks of the indigenous slaves chained to a short brutal life in a mine, never seeing the daylight, in order to produce the altarpieces of a Spanish cathedral. It’s not that the artistry of post-imperial Europe isn’t beautiful but the history behind it complicates, implicates, obligates. (That’s why I’ll stick with my pre-colonial Europe, the medieval world before the Renaissance.)

In Roberto’s horrifying/hilarious roadtrip in the Balkans, one of their party has a hapless misadventure leaving them all to wonder if they’re in trouble with the authorities. I drew inspiration from a more minor misadventure: I drove on top of a sheep sleeping in the road, out of its pasture, after the crest of a hill. Should we stop and attempt to find the shepherds? Suddenly the drama of a angry peasant shakedown, a possible police involvement (only so they could share in the baksheesh expected of the assumed-richer Western Europe-tourists), not to mention the safety of the females in the party… led us to drive away. For a night we experienced the paranoia of the fugitive, seeing the local Balkan police everywhere, the locals staring holes in us. I still wait for the knock at the door: INTERPOL would like a word with you… a glowering Albanian shepherd standing behind the officer, on the verge of justice.

I feel my generation and I may have enjoyed the last era of a more carefree, affordable Europe. My trips go far back as two family vacations (the 1970s) and the golden backpacker-hostel era (the 1980s). Remember there was such a book as Europe on $5 a Day? From twenty years ago, I remember $8 hostels and bunk rooms, showers down the hall, and breakfast-lunch-dinner from food-truck crepes, slices of pizza, kebabs, and gelato sugar highs, coming in at under twenty additional dollars… the $30 a day Europe. Food remains a bargain in Europe, but everything post-Covid is pricier and adult pleasures (a nice hotel, en suite toilets) will run you some money these days. I pretend that I am capturing a certain golden era of Europe travel… but it is more likely that all I am depicting is what it means to be young, young and in a foreign country, where the drab real life back home. with its bills and its cares, can be safely packed away and forgotten for a summer.